As I sit chained to the antibiotic IV bag in the sterile armchair of the infusion ward, I track the progression of the seasons changing. From the window, I watch the September greens turn to October reds, lamenting the lack of difference in my physical composition. I track the days of my treatment like leaves falling from those trees, hoping my exposed trunk is resilient without its protective coating. On the days I’m more lucid, I spend the thirty minutes of treatment writing poems to ration my fate. A fate so different from my classmates up the hill, making their way to lecture and chatting about light problems, subconsciously knowing they have easy resolutions.

During move-in week at Wesleyan University this September, I ignored my body’s warning signs for one day too long. Determined to ignore the fever I had been nursing for a week and to get on with my senior year of college, I let a life-threatening blood infection multiply inside my veins. One night, with an alarmingly high fever of 103.2 and a migraine so strong I thought a Greek god would spring from my head, I let my roommate drive me to the ER.

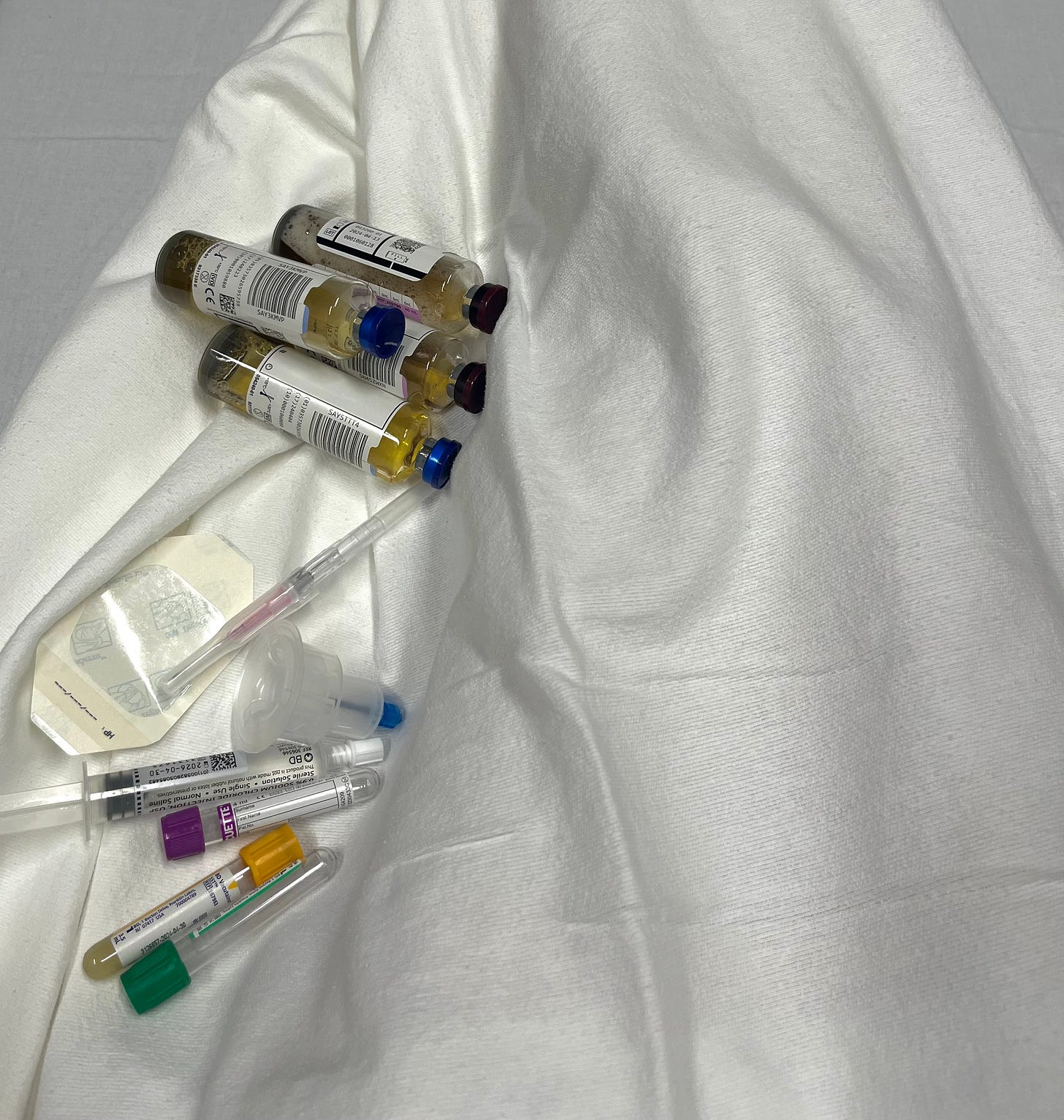

The chipper nurse, Josh, did his best to calm my nerves as he retrieved vial after vial of blood, running tests that would eventually warrant my three-night stay at Middlesex Hospital. All my doctors emphasized how lucky I had been to “catch it in time” and “avoid serious complications,” but as it turned out, I had let the infection fester long enough to warrant a month of intravenous antibiotics. Medication that needed to administered in the infusion ward seven days a week. It’s where I find myself now writing this sentence, a steady pulse of pharmaceutical cocktail entering into my left upper arm.

My phone dings. The text reads, “How are you?” The sender, a blurred amalgamate of all my friends and family, doing their duty to hold me. I am thankful for my support system in such moments, texts arriving daily and routinely. But how does one even begin to respond? “I’mokbutamomentagoIfeltlikemyfeetwouldgiveoutandmybrainwouldexplode.” Too much. Perhaps a simple “I’m feeling a bit better,” or “Almost semi-normal again,” or “Physically better. Mentally Mixed bag,” or “The climb is slow, but we are climbing.” My texts mimic the same things I tell my friends in person. Short fragments that give an outline of my condition, drawn to keep people informed but outside. Being ill is not a state you want to share. Even though my prognosis is not passable, I wouldn’t want those around me to catch the bug of untimely misfortune.

Aside from sparse language, I like to inform my friends by coating my pain with humor. “I’m ok. But I wish I hadn’t just cut my hair short. I look less like Julie Andrews and more like a fresh dose of chemo.” These quips assure my friends to be worried, but only slightly. If she can still make jokes, she’s surely okay enough. An acknowledgment of a problem but an ineptitude to solve it, like a sugar-coated lozenge. Temporary relief instead of cure, I picture them departing our catch-up lunch to go to class, the taste of my condition slipping down their throat and out of sight.

But who am I to fault them? In their position, I would most likely do the same. Language cannot bridge certain gaps, gaps made pronounced by unshared experiences. “I’m in pain” might as well be the same as saying, “My head feels like milk bubbling over an unwatched pot.” Descriptors fail when circumstances are incongruous. To live in a young and healthy body is to be intrinsically ignorant, an ignorance that no empathy can reconcile. Good intentions are not enough to mend the differences in attitude: my peers routinely reject their bodies as my body routinely rejects me. My peers seek out substances to blur their senses, while I seek out medication to grasp at shreds of cognition. My words of caution do nothing to prevent my fellow collegians from filling their lungs with smoke and their livers with toxins. My stories of hospital life fade as they eat less and drink more, consuming like their bodies will be resilient for the rest of time.

Luckily and unluckily, I have someone who can relate to me and empathize in the way I crave so desperately. That person is my father, who, similarly to me, has spent his fair share of time in hospital rooms this past year. In a jarringly proximate span of time, my father and I have experienced many of the same sensations, although to different extents. His hospital stay was much longer, and his arms were poked at tenfold, yet we have both felt the inexplicable fear that comes with a body abandoning its spirit. So, when I wake from a racing heart, I turn to my father for a truly perceptive ear.

One day, shortly after hospital discharge, my email pinged with a message from him. The subject line read “a poem for a poem,” and the email contained a Word document with his latest piece entitled “I Try to Follow:”

I Try to Follow

his mind. It races like a car

with words about to crash.

What’s on the board seems scribble,

many marks tied together, holding to the line.

The text is no better, with thoughts so leaden

pages stand still.

Everything is determined. Reality is subjective. Or not.

Truth is the sum of some numbers

or part of Benjamin, Chomsky or Derrida’s views.

I am exhausted searching for the core.

Why wake with all the blankets thrown to the floor

when all you want to know can be found

listening to Bessie Smith sing the Blues.

Moved by his language, the scarcity of words spoken to my friends suddenly came flowing back like an untapped well. Feeling so isolated, I forgot that my experience, although unique in many respects, was not singular. While no person’s pain is the same, my plight was close enough to my father’s that I could speak without repression, and express without miscommunication. Obliged by the email’s subject, I responded with a poem of my own:

Coban

The labels on the cabinets read as follows

“Empty”

“Empty”

“Coats”

“Tape,” “4x4 Gauze,” “Alcohol wipes,” “Kleenex,” “Kidney Trays”

“Pillow Cases” “Misc. Bandages” “Coban”

Coban?

CO-BAN?

What could that be?

Pinky promises between toddlers

We will never never have another best friend!

Promise?

Promise.

Cuban?

With a typo?

Cigars confiscated from the chronic smoker

getting chemo in the room over

A muted voice calling to the nurses.

Can I – get a —cup of coffeey?

Coban.

Tylenol for the particularly unfortunate

For those who have to discuss

Alternative possibilities

A different treatment plan

A way to move forward.

Coban.

I had to ask the nurse

my curiosity eating me alive

like the bacteria in my blood

A girl obsessed with consumption,

of having her cup too full.

Coban.

A beige bandage,

ridged and pruned

like the skin of my ward-mates.

Real army camouflage

For those who hunt the beast of their health.

To my father, I’m thankful for many things. But now, I am especially thankful for his ability to share and receive words. I’m constantly amazed by his unwavering commitment to expression and for reminding me that the only way to move through hardship is to wade deeply inside it. To find peace in the murky waters of the mind, one would be wise to fish words from its depths. “It’s all about the little victories,” my father says after putting a poem to rest, finally finding the proper adjectives to describe the indescribable. But to find the right words and the right ears is more than a little victory. It is a triumph. To uncover a shared language, one must feel pain deeply and unveil reality despite its challenges. In the storm of the past few months, my father provided me with a lifeboat, its mast built from metaphors, its stern from simile. I’m not sure I will ever be able to find the words to thank him, but I’ll be damned if I don’t at least try.