On the first day of fifth grade, my slender and stoic English teacher, Ms. Paglioca, wafted around the class handing out stacks of Post-it notes. “You’re all old enough now,” she said in a haughty voice, “to start annotating your books.” She made it sound rather bleak, like some duty we had been sentenced to—young academics fledging their first bonds to institutional ordinance. “From now on, when you read a chapter for homework, I expect all of you to come back to class with at least five annotations.” The Post-its, we would learn, were to preserve the sanctity of the page. “How would you feel if you opened a book and the pages were all scribbled on?” Ms. Paglioca asked, as if her rhetorical question was some magnanimous bit of wisdom.

The book we were reading at the time was Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. I remember setting up my workstation, the goody-two-shoes that I was, and unearthing my Post-it stack like some talisman of adulthood. I was excited to read properly and dove into the first chapter. I discovered, rather quickly, my distaste for the Post-it method. All I wanted to do was underline and circle, to press the inky conduit of my thoughts onto the pages before me. “Write any unknown vocabulary in your notebook,” she had said. But there was so much that I found it disruptive to have to tear myself out of the page and into my notebook. I longed for the sweet release of a quick circle.

It took some time to deprogram my teacher’s early commandments. But when I was old enough to realize there was no “right way” to read a book, I quickly developed my own annotation method. Now, I circle words and phrases that are unique or particular, and I underline sentences that I perceive to be narrative glue, thematic context, or a parcel of insight I had been trying unsuccessfully to pin down in my head. When I write in the margins, it’s a word or two that acts as a checkpoint—a way of anticipating what a future me will go looking for after a first read-through. Annotating, as someone with auteur aspirations, is by and large a way for me to pull out techniques and sentiments I hope will inform pieces of my own.

In the last few hours ahead of a trip, while I’m at home killing time before the airport, I usually survey the bookshelf in my living room for titles to add to my suitcase (everything is fair game except hardcovers—I’ve paid the price for their sturdiness at check-in one too many times). I’m lucky to have a father who, throughout his life, has moved his print collection with him from home to home, the bookshelf always full of his favorite copies, so numerous I have only started to skim the surface of the collection. On this occasion, I pulled out Numbers in the Dark, a collection of fables and short stories by Italo Calvino, We Are Not Ourselves by Matthew Thomas, and To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf.

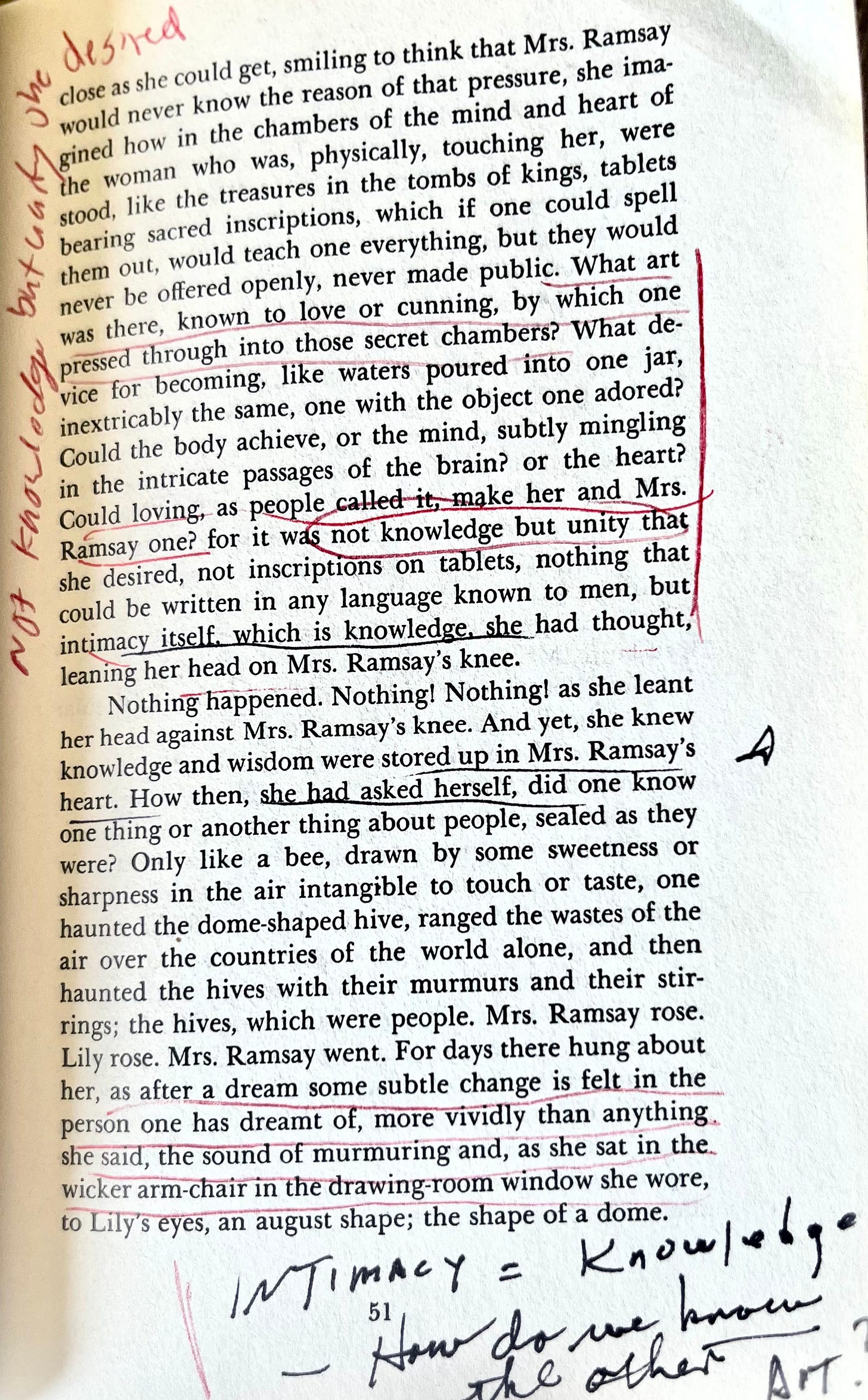

As I sat alone on the beach today, a storm brewing on the horizon, I felt it apt to start To the Lighthouse. It’s my first time reading Virginia Woolf (gasp!), and needless to say, I’m no longer lost at sea (sorry I had to). I was also delighted, as I often am, to find that the book had already been annotated by my father. Some pages are blank, some covered in his pen marks. I read, partially influenced by the things he has deemed important enough to amplify in red and black. Page fifty-one is particularly penned, a page that reads:

What art was there, known to love or cunning, by which one pressed through into those secret chambers? What device for becoming, like waters poured into one jar, inextricably the same, one with the object one adored? Could the body achieve, or the mind, subtly mingling in the intricate passages of the brain? or the heart? Could loving, as people called it, make her and Mrs. Ramsay one? for it was not knowledge but unity that she desired, not inscriptions on tablets, nothing that could be written in any language known to men, but intimacy itself, which is knowledge, she had though leaning her head on Mrs. Ramsay’s knee.

In this section of the text, Woolf shows us the mental machinations of Lily Briscoe, a young and unmarried painter who is summering with the Ramsay family. Lily loves them to the point of reverence, especially Mrs. Ramsay, their beautiful matriarch. In a moment of tenderness between the two women, Lily muses on the uncrossable depths that lie between two estranged spirits.

In the top left margin of the page, I write:

NOT knowledge but Unity we desire (written so that it climbs up vertically and croons over the top border)At the bottom of the page, my father writes:

Intimacy = knowledge

— how do we know the other

Art?I pause to let the two sentiments stew. While Woolf’s words themselves have a way of baking into my brain, what I took most from the page was how wonderful it was that, in the act of annotating together, I in the present and my father in the past, have found this ineffable unity on the page. What profound intimacy it is, then, to share books scrawled with the traces of our own secret chambers—to read a book in the second degree, already filtered through a consciousness we know and continually hope to know better.

I even love reading books annotated by an unknown hand—someone whose etchings made it past the used bookstore teller. In those instances, I have the pleasure of drawing up a character largely through a game of read and tell, weaving together a picture of someone I’ll never know, based solely on the words and sentiments they felt drawn to highlight.

It’s an appeal I leave you with, then—a solicitation to get off your computers and Kindles, pick up a book, and write in it like a journal. Then give me your book—strangers, friends, and family alike—and I’ll give you mine in return. Because sometimes our own words are not enough to adequately convey the depths of our knowledge, our attempts toward shared intimacy. Because sometimes it’s best to let Virginia Woolf speak for us and let our pens trace the contours of thoughts we have yet to fully understand.

1) I love how you write the every day details of life. 2) I have a friend who loves to annotate, wants us to read & annotate the same book and then swap in lieu of a (verbal) discussion. I reluctantly agreed, but now I'm sort of looking forward to it.

Beautiful gemma